A friend of mine sent me this video about three years ago, and it's bothered me ever since, but not in a nice, orderly way. My problems with it were all in a jumble, and I couldn't straighten them out. I tried to supplement my understanding of it with extra research, but then I looked at the last time I published a blog post, looked at my backlog of other posts, and decided, "Nah, I'm just gonna get this over with, because I don't think I'm going to need much more than a play-by-play critique".

With all that in mind, this is all stuff that I've heard from who-knows-where. If I specifically looked anything up for this post, I've linked it; if it's just something I took from my memory from the fifteen+ years I've spent reading Tolkien, then it's not linked, and therefore may be wrong and definitely is not authoritative.

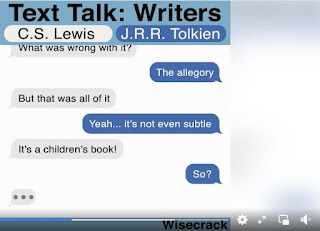

The video, in case you haven't clicked on the link, is a Facebook video that shows a pretend text conversation between Lewis and Tolkien on the subject of allegory. Tolkien famously said he "cordially disliked allegory", but this fictitious CS Lewis challenges that with some examples from Lord of the Rings and the Silmarillion. I'll put in some screenshots so you can see what I'm critiquing.

First off, there was this:

Those words--allegory, influence, symbolism, and parallels--are not the same things. They are not (necessarily) interchangeable. Tolkien said he disliked allegory, but not symbolism, parallels, and definitely not influence. At least once (I think in the prelude to the first reprinting of the Lord of the Rings?) he openly said that his Catholic beliefs influenced his writing, at first subconsciously and later consciously. In other words, his beliefs were so strong for him that he couldn't possibly create a world without them. His beliefs influenced how he imagined a world would work. But that doesn't make it an allegory for those beliefs. (Granted, symbolism and parallels are very similar to allegory, but I'm not going to delve into those.)

Tolkien defined an allegory as a story where the author gave the reader no room for interpretation as to what things mean. The story means what it means, and it cannot be interpreted. The best example I can find of this conflict is Liam Neeson's performance of Aslan. Under the character's description on Wikipedia (for Prince Caspian), it says that Neeson viewed Aslan as "the spirit of the planet—this living, breathing planet". Nope--Neeson is wrong, because Aslan is Jesus and allegory (in Tolkien's view) removes interpretation and applicability. (All of that, plus the earlier quote about disliking allegory, is in this video: Tolkien and Allegory - YouTube).

Now, when something influences another story, that doesn't remove the reader's interpretation. It just means that someone heard Story A, liked parts of it, and worked it into their story. But that does not remove the reader's ability to draw an application that has nothing to do with Story A.

Now, let's move on. This next section just requires a basic knowledge of Catholicism, history, and the stories themselves.

WWI and War of the Ring

Gandalf, Resurrection, and Jesus

This one looks good on the surface, but it's pretty obviously not true. First off, if the only thing that Gandalf has is that he comes back to life, then how do we know it's Jesus? Why not Lazarus? Or the widow of Nain's son? Or every believer after Jesus returns?

Returning to Tolkien's point about allegory, there's not nearly enough similarity to force this to be Jesus. There's nothing about dying for sins, which is rather crucial.

Also, the idea of Gandalf being Christ... well, Gandalf resurrected and became Gandalf the White because he filled Saruman's void... so, does that mean that Jesus resurrected because there was some other god whose void he had to fill because the other god turned evil? That's some pretty serious heresy that Tolkien would never have disseminated.

Aragorn and Frodo

They way they say this, it sounds like the parallels should be obvious, but I have no idea what these allegorical elements could possibly be. Aside from the generic insert-yourself into the heroes, like most fantasy stories have, I'm stumped.

Aragorn's assumption of the kingship is terribly similar to the four Pevensie children becoming the kings and queens of Narnia, and I've heard in places that it's influenced by Tolkien's study of the Anglo-Saxons' beliefs (he studied Anglo-Saxon culture), but that hardly qualifies for what the text message was talking about.

Dwarves and Jews

The idea here being that the Jews had access to the promise of the Messiah before other people did, but... that's so not what the story of the Dwarves is.

The Dwarves were created by Aule and not by Eru (the god-like character of Middle-Earth). Aule got impatient for the Elves to be created and really wanted someone to teach, so he jumped the gun, circumvented Eru's orders, and tried creating his own species. When Eru caught Aule creating a separate race, he punished Aule by putting the Dwarves to sleep and not allowing them to wake up until after the Elves woke up. That's pretty much the opposite of the story of the Jews.

Not that it's impossible that the story of the Jews influenced the story of the Dwarves. I... don't know how it would have, because they're terribly different stories and because Tolkien also took inspiration from Finnish, Norse, and Anglo-Saxon mythology and the Dwarves' story might have come from them (although I don't know enough about those stories to give any examples).

Environmentalism and Industrialization

This is the best point they make, and the one that can't be explained with just a basic knowledge of what Tolkien knew about industrialization and environmentalism. I will say that to me it would be a terrible, horrible allegory for industrialization, for two reasons: first, industrialization has upsides, such as medicine, that are only briefly explored in the books (the Uruk-hai cure Merry and Pippin when they've been captured), and Tolkien's alternatives--magical aethelas plants that can only be used by the king--don't have a good or effective comparison in the real world; and secondly, the "fight against industry" is an external fight (one kingdom vs. another kingdom), while the arguments about industrialization are extremely internal fights (struggles that each country needs to sort out inside its own borders), and making it a nation-vs-nation fight just takes away all the serious nuances that are integral to that debate. The thing is that I don't know for sure that Tolkien cared about all of that. I can't imagine he didn't, but I don't know he did.

What I will also say is that this still doesn't fit Tolkien's definition of allegory because there are alternative interpretations. When Isengard turns into a war citadel, not only do the forests disappear, but the area begins to look more like Mordor, and to me, that is the key point--its alliance to Mordor makes it look more like Mordor. I read somewhere that Tolkien believed that, in a story a place or thing made with good intentions couldn't possibly have an ugly appearance (page 62 in the version I used for my English thesis; I'm not sure if that's the same version). Isengard was originally beautiful because the intention of the builders was for good; however, as Saruman's intention took over the building, that good appearance faded along with the intention.

All things considered, I realize this is a sloppy and paper-thin post, but that "Gandalf=Jesus" comment made me not care that much.

No comments:

Post a Comment