In honor of Professor Tolkien's birthday, I thought it was time for another Tolkien post! (Is this going to get published on January 3rd? No, no it won't, but oh well.)

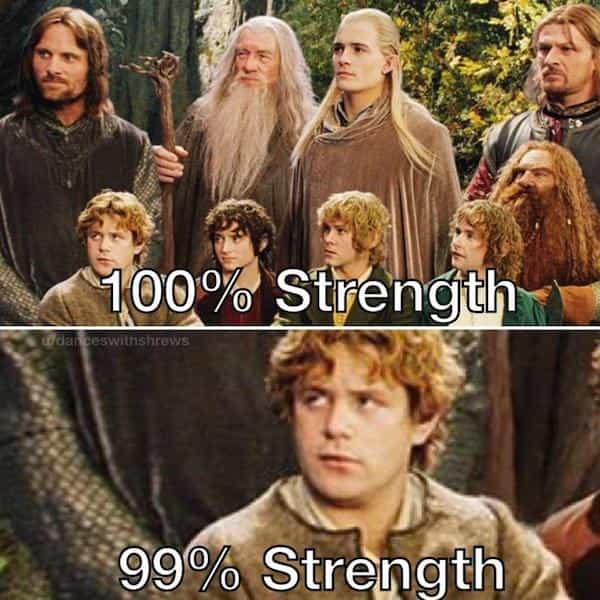

The Tolkien community online is full of thoughts, comments, and of course memes that showcase Sam's importance to the Fellowship and his strength of character. Memes like this one:

And this one:

And of course, this one:

|

| (Okay, this isn't the one I was looking for. The one I was looking for also had Aragorn with a machine gun and Gandalf doing something. But the idea is generally the same.) |

Now, far be it from me to disparage Sam himself. Sam carried a set of cast-iron cookware over mountains, past a giant spider, and into Mordor, for goodness' sake. He supported Frodo and helped him carry on when the Ring was sapping all Frodo's strength. Sam is awesome. I am, however, moderately disquieted by the way these posts praise Sam at Frodo's expense. They tend to miss the significance of Frodo's contribution in a way that fantasy, as a genre, has been missing Frodo's and Frodo-like characters' values and contributions for a long time.

Oddly enough, the critiques of Frodo that I hear day-to-day usually have to do with him being a wimp, him whining a lot, or of him being constantly carried through his mission. However, in Tolkien's day, there seemed to be a far more serious criticism of Frodo: Frodo failed his quest. I'd never thought of this until I stumbled across this video; watching it instantly put me in mind of all the modern disdain for Frodo.

But when you recognize that Frodo failed, you recognized why the quest succeeded; and when you recognize why the quest succeeded, you can see how Frodo was absolutely a necessary part of the quest, and that Sam would have failed the quest without Frodo.

Frodo failed because, at the very end when he stood in the center of Sauron's power, he was too weak to defy Sauron--too weak to defy the thousands-years-old demigod, the most powerful being left in Middle-earth after Morgoth was defeated. Frodo failed at the moment when everyone would have failed, because no one was powerful enough to defy Sauron in the center of his power. But then, out comes Gollum, who fights Frodo for the Ring, wins the fight, and then falls into the lava, dying but destroying the Ring. Even though the questers failed, the quest succeeded.

But why was Gollum there? Gollum was there because Frodo spared his life and took him on as a retainer.

Consider in The Two Towers, when Frodo and Sam have first truly met Gollum, Sam's instinct is to tie him up so he could not follow them, but Frodo remembers Gandalf telling him that Bilbo pitied Gollum and so didn't kill him; Frodo says, "But still I am afraid. And yet, as you see, I will not touch the creature. For now that I see him, I do pity him" (601).

It's interesting to me that the book highlights how Frodo is still afraid. This mercy isn't wimpiness; it's not easy for him to show mercy. And yet, he does.

Shortly after, when Gollum tries to escape, Sam digs out his rope and says, "You nasty, treacherous creature. It's round your neck this rope ought to go, and a tight noose too" (although when Sam tied the knot around Gollum's ankle, Frodo discovered he was gentler with the rope than with his words) (603). This theme continues; in the Dead Marshes, Sam remains untrusting of Gollum and tests him before falling asleep (609), names him "Slinker and Stinker" in his mind (624), etc. Not that Sam is proven wrong, mind you. You know how the second movie ends with Gollum deciding to lead the Hobbits to Shelob--after the Dead Marshes, after the Black Gate, after the drama with Faramir? In the books, that conversation happened much, much sooner, even before they reached the Black Gate (618-619). Sam understands Gollum well enough and is right that he cannot be trusted. But again, if Sam had his way, the Ring never would have been destroyed.

Tolkien talks about Sam and Frodo in some of his letters to his readers, highlighting the value both of them carry in the story. In letter 184--to a man named Sam Gamgee, ironically!--he describes Sam as "a most heroic character" (not the most, but still a hero). Actually, you should read the entire letter, as it is delightful.

Then in letter 191, he says this:

If you re-read all the passages dealing with Frodo and the Ring, I think you will see that not only was it quite impossible for him to surrender the Ring, in act or will, especially at its point of maximum power, but that this failure was adumbrated from far back. He was honoured because he had accepted the burden voluntarily, and had then done all that was within his utmost physical and mental strength to do. He (and the Cause) were saved – by Mercy: by the supreme value and efficacy of Pity and forgiveness of injury.

...There exists the possibility of being placed in positions beyond one's power. In which case (as I believe) salvation from ruin will depend on something apparently unconnected: the general sanctity (and humility and mercy) of the sacrificial person. I did not 'arrange' the deliverance in this case: it again follows the logic of the story. (Gollum had had his chance of repentance, and of returning generosity with love; and had fallen off the knife-edge.)

[...]

No, Frodo 'failed'. It is possible that once the ring was destroyed he had little recollection of the last scene. But one must face the fact: the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures, however 'good'; and the Writer of the Story is not one of us.

In this letter, Tolkien made it extremely clear that Frodo did indeed fail at Mount Doom. How could he not? Now, the mercy that Tolkien highlights in this letter is the mercy from the Writer of the Story (he doesn't say God, but I get the impression that's close enough) which is shown to Frodo: Frodo is shown mercy, even though he failed, because he had, as far as he could, poured in all his effort. Gollum's role here is shown as the logical point in which Frodo is rewarded for his prior virtues--the only way for the quest to succeed.

In 192, he highlights some very similar details:

It is possible for the good, even the saintly, to be subjected to a power of evil which is too great for them to overcome – in themselves. In this case the cause (not the 'hero') was triumphant, because by the exercise of pity, mercy, and forgiveness of injury, a situation was produced in which all was redressed and disaster averted. Gandalf certainly foresaw this.... But we are assured that we must be ourselves extravagantly generous, if we are to hope for the extravagant generosity which the slightest easing of, or escape from, the consequences of our own follies and errors represents. And that mercy does sometimes occur in this life.

Frodo deserved all honour because he spent every drop of his power of will and body, and that was just sufficient to bring him to the destined point, and no further. Few others, possibly no others of his time, would have got so far. The Other Power then took over...

To the destined point, and no further. I love that phrasing. In this letter, Tolkien is again specific that "pity, mercy, and forgiveness of injury" are the causes of success. It's not about strength, because no one's strength could possibly have prevailed against Sauron, but Frodo's mercy created a situation beyond Sauron's power to control.

But letter 246, in addition to being the longest letter I'm quoting, has, what I think, is the most important of Tolkien's observations (emphasis mine):

Frodo indeed 'failed' as a hero, as conceived by simple minds: he did not endure to the end; he gave in, ratted... [Simple minds] tend to forget that strange element in the World that we call Pity or Mercy, which is also an absolute requirement in moral judgement...

I do not think that Frodo's was a moral failure. At the last moment the pressure of the Ring would reach its maximum – impossible, I should have said, for any one to resist, certainly after long possession, months of increasing torment, and when starved and exhausted. Frodo had done what he could and spent himself completely (as an instrument of Providence) and had produced a situation in which the object of his quest could be achieved. His humility (with which he began) and his sufferings were justly rewarded by the highest honour; and his exercise of patience and mercy towards Gollum gained him Mercy: his failure was redressed.

What I find interesting about this letter is that Gollum is no longer just an incident which logically leads to the Ring being destroyed, but rather his appearance at Mount Doom is a direct reward for Frodo's mercy toward Gollum. Moving on, from the same letter (again, emphasis mine):

Sam was cocksure, and deep down a little conceited; but his conceit had been transformed by his devotion to Frodo. He did not think of himself as heroic or even brave, or in any way admirable– except in his service and loyalty to his master. That had an ingredient (probably inevitable) of pride and possessiveness: it is difficult to exclude it from the devotion of those who perform such service. In any case it prevented him from fully understanding the master that he loved, and from following him in his gradual education to the nobility of service to the unlovable and of perception of damaged good in the corrupt. He plainly did not fully understand Frodo's motives or his distress in the incident of the Forbidden Pool. If he had understood better what was going on between Frodo and Gollum, things might have turned out differently in the end. For me perhaps the most tragic moment in the Tale comes in II 323 ff. when Sam fails to note the complete change in Gollum's tone and aspect. 'Nothing, nothing', said Gollum softly. 'Nice master!'. His repentance is blighted and all Frodo's pity is (in a sense*) wasted. Shelob's lair became inevitable.

This is due of course to the 'logic of the story'. Sam could hardly have acted differently. (He did reach the point of pity at last (III 221-222)4 but for the good of Gollum too late.) If he had, what could then have happened?... I think he would then have sacrificed himself for Frodo's sake and have voluntarily cast himself into the fiery abyss.

The rest of the letter deals with how other characters would have used the Ring to defy Sauron, and it's actually quite interesting, so I encourage you to read that, also.

But all of this excerpt shows why the Ringbearer had to be Frodo: he was the one who best understood the concept of mercy in a way Sam didn't grasp. Partly thanks to the example set by Bilbo in The Hobbit, and partly thanks to Gandalf's mentorship in Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo is the one who committed the action that made the quest succeed--long before he reached Mount Doom. Tolkien expressly criticizes Sam's harsh judgment, even though he recognizes Sam's courage in letter 184, and specifically points out that it endangered the quest rather than protecting it.

It absolutely fascinates me that the action critical to success in Tolkien's great epic is mercy and forgiveness, and I'm moderately irritated with myself for not recognizing it sooner. It's super easy to get lost in the general epicness of Aragorn, Boromir and Faramir, the Rohirrim, the constant fighting, the mumakil and the Nazgul, and so on. But ultimately, none of that would have been worth anything if Frodo's quest had failed, and Frodo's quest would have failed without that act of mercy.

And yes, I started writing this on January 3rd and finished it on August 6th. Go figure.

No comments:

Post a Comment